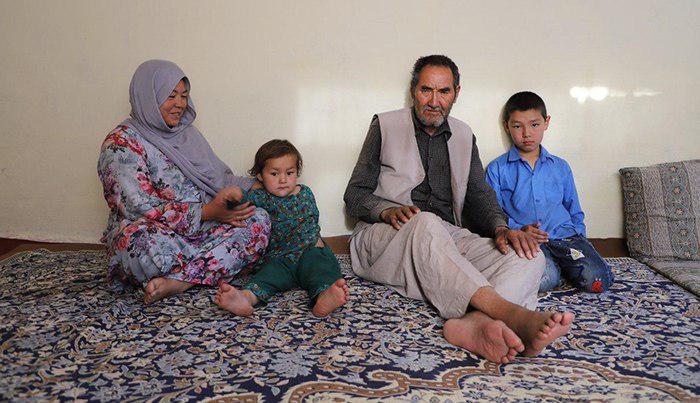

The 75-year-old Abdul Hussain, who has been suffering from severe rheumatic diseases, is a longtime unemployed. Living in a mud-house in slum neighborhood of Barchi, Kabul, Hussain carries the heavy burden of a household—his spouse with two young children, a four-year-old daughter and an eight-year-old son. Every dawn he leaves his somber house for Naqash station where he waits for hours for a day work offer. As the sun sets, he goes back to his house, empty handed and with a deep sense of guilt.

Abdul Hussain, however, is not the only unemployed man in the city. There are thousands of jobless men who are struggling to make living. Thousands of young and old day-rate workers rush to public places as the sun rises in the capital Kabul, and empty handedly return to their houses as the sun sets. The city takes a different look when in hot summer days, the day-rate workers, with unhappy faces, go back to their homes.

In a sunny September day as the wind was blowing softly, the shopkeepers were busy opening their shops, and school girls were walking in laughter, I made my way to a crowd of workers who were waiting in Naqash station. Staring at an unknown direction, a worker, leaning on his bicycle, had sank in deep thoughts. Another one had lied in the shadow of a wall, putting his plastering tools beneath his head. I immediately found myself surrounded by a swelling crowd of workers. They were rushing to take an opportunity and talk to me as if I was looking for worker.

Breaking the crowd, a man made his way and asked me, “what’s up? I can work if you are looking for a labor?” Fearing to miss a potential opportunity, he continued—not letting me speak–, “I can do every work; plasterwork, stonemasonry, painting walls.” Pointing to my camera, a worker told him that I was not looking for worker. Scratching back of his neck, he felt taken aback.

“I want to interview,” I said.

He was Mohammad Zia. Living in Qalai Naw, a remote western neighborhood of Kabul city, Zia is father of four children. He will be very lucky if he can find a day labor in a week. Having labored for four years, Zia has not been able to make a new clothe for himself. All he earns is spent to provide very basic need of his family.

We fell in conversation but was interrupted by a young man shouting that “Down with Ashraf Ghani. He is behind all our miseries.” The crowd broke out. A man, who had fallen down, became unconscious. “See, this is because these people do not have anything for breakfast.” A man standing nest to him told me. Few people took him to shadow of a wall.

I left the crowd, and sat next to an elderly man who was busy tying his shoelace. His hands, which were hardboiled by years of hard labor, were big. “You are just caring for your own business. Every day, people like you, come to us, but nothing changes and we are still struggling with ordeals,” the man said when he found me sitting next to him. I had nothing to say, feeling embarrassed by mountain of helplessness, and walked ahead.

As I waked ahead, I happened to see Abdul Hussain, lying lonely in a corner with swollen ankles and feet hardly pushed into his torn and tattered shoes.

Hussain cannot easily bend his legs and he cannot walk comfortably as he is struggling with severe pain caused by rheumatism. All he does is for his eight years old son: Hadi. Talking to me, he was looking to different directions as if looking for someone to come and offer him a day labor. Moments later, with painful, and broken heart, he asked me “do you want to talk here or go to my home, there are many things inside me, and I want to pour them out?”

“Wherever you feel conformable,” I responded.

Putting his gunny sack full of, perhaps, working tools, on his back, Hussain told me that his house was close to the area and in the neighboring alley.

The 75-year-old Hussain, toddling like a young child, was eager to speak his heart and mind as the two of us were walking toward his house. The house owner asked me last night for monthly payment. “I don’t have,” I told him. “The landlord has asked me to get out his house.”

He entered into a yard which was engulfed by apricot and apple trees. There was a well in the middle with bucket and pitcher beside it. Three families were living in the campus. Hussain’s house, with a large window, was the smallest one which was damaged by rain falls. Hussain’s wife and her four-year-old daughter, Bahar, welcomed us. I entered in the room, squatted on a mattress, and listened to Hussain’s painful story.

Living for several years in Iran, Hussain returned to Kabul soon after the Taliban regime was toppled by the American forces.

“When I return home at nights, she runs to me and asks if I have bought her anything,” Hussain says, pointing to his daughter Bahar. “I feel deeply embarrassed and I wish the earth opens its moth and swallows me up.”

“I feel deeply embarrassed and I wish the earth opens its mouth and swallows me up.”

The 75-year-old Hussain says.

In his 50, Abdul Hussain got married. “I made a big mistake for I left Iran. I had a good work there,” he regretted, complaining that he had not received any assistance from the United Nations.

Sitting cross-legged and leaning it on the wall, he showed some of his youth photos showing a young hefty and broad-shouldered man. No one could believe that the young broad-shouldered man in the picture, is now struggling to earn a living.

Hussain’s spouse is doing embroidery to make money. She complains about slowdown in market, saying there are not costumers to her products. “No one uses them (her embroideries) any more. It can just help me buy some pen and notebooks for Hadi,” she said.

Hadi’s notebooks were filled with colorful drawings in which Afghanistan’s flag seemed much highlighted. I asked him if he loved Afghanistan. “I love Afghanistan,” he answered with a childish tone.

As I was leaving Hussain’s house, he excused himself, and humbly said, “Please do something for us if you can.” A deep feeling of helplessness pervaded my mind as I heard the humble call for help by a 75-year-old helpless man who is limped under the heavy burden life in a city with a high unemployment rate.

This story has been developed by Masooma Erfan and translated by Mokhtar Yasa.